Beyond Rauser's View: Solving OT Violence with Covenant Virtue Ethics

Let's face it. Biblical violence is one of the most challenging moral and theological dilemmas for Christian faith. When passages describe God commanding Israel to "destroy [the Canaanites] totally," "show them no mercy," or details the slaughter of "men and women, children and infants," we confront a serious tension: How can the God revealed as perfectly loving and just also command actions that appear genocidal?

Introduction: The Theological Dilemma

Randal Rauser (2009) powerfully frames this challenge through a logical argument that results in an apparent contradiction:

- God is the most perfect being there could be.

- Yahweh is God.

- Yahweh ordered people to commit genocide. [Based on a surface reading of certain OT texts]

- Genocide is always a moral atrocity. [Based on moral intuition/modern understanding]

- A perfect being would not order people to commit a moral atrocity.

- Therefore, a perfect being would not order people to commit genocide. (from 4, 5)

- Therefore, Yahweh did not order people to commit genocide. (from 1, 2, 6)

This valid argument creates a direct contradiction between premise 3 (the apparent textual claim) and conclusion 7 (the necessary theological conclusion based on God's perfection). A skeptic might use this to argue against God's existence or goodness. As Christians committed to both God's perfection and Scripture's authority, we must resolve this contradiction. Rauser and I both ultimately affirm conclusion 7 (Yahweh did not order genocide as understood in premise 4) over premise 3 as typically interpreted, but we arrive there via different paths.

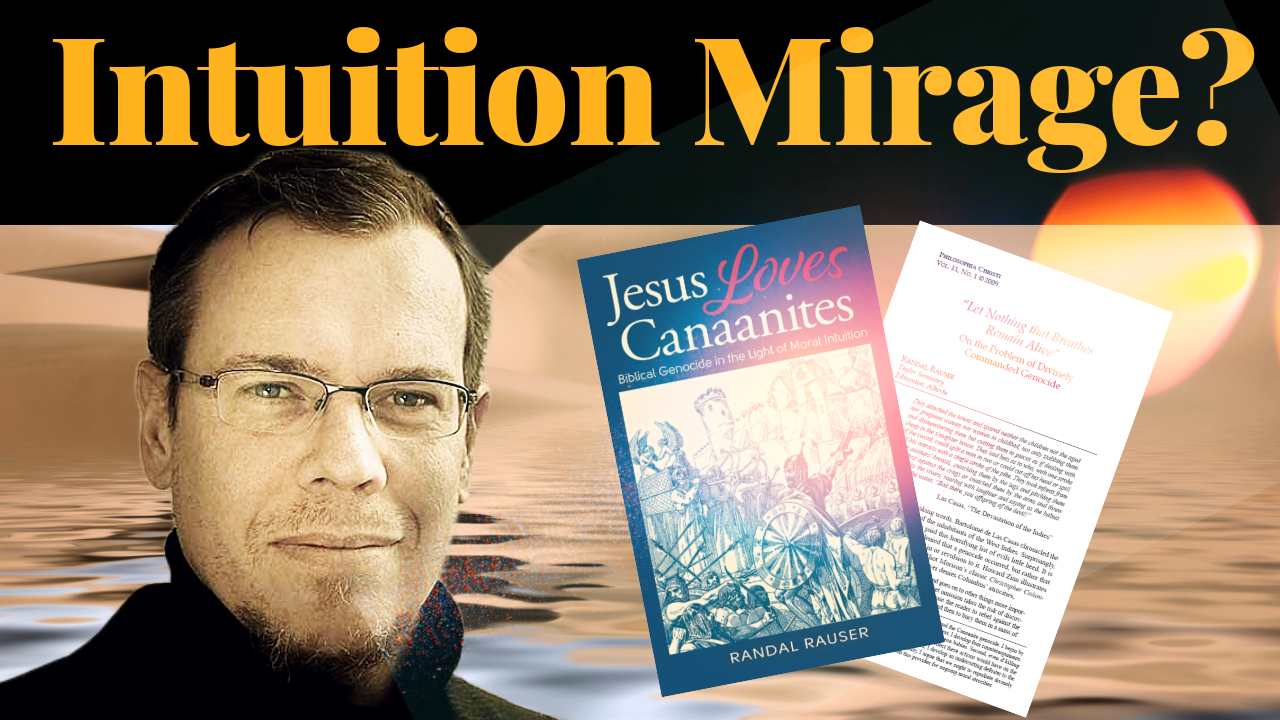

In his book Jesus Loves Canaanites, Rauser proposes a solution he calls "Providential Errancy Theory" (PET). PET resolves the contradiction by rejecting premise 3 outright: it argues that the biblical texts, while inspired, are in error in reporting that Yahweh actually issued such morally atrocious commands. God, according to PET, providentially allowed these errant human perspectives into Scripture for pedagogical purposes.

A Glimpse at My Solution

In this article, I will critically examine Rauser's PET and propose an alternative framework: Covenant Virtue Ethics (CVE). CVE provides a more theologically coherent and hermeneutically responsible solution. CVE also lands on conclusion 7 (Yahweh did not order genocide-as-atrocity) but rejects premise 3 as formulated on interpretive grounds, not by claiming textual error.

Here’s a preview of CVE’s resolution of the logical dilemma. CVE maintains both God's perfect character (P1, P2, affirming C6 & C7)—understanding that perfection encompasses the full, complex divine nature revealed in passages like Exodus 34:6-7 (including both profound love and unwavering justice)—and the integrity of Scripture as God's reliable self-revelation (challenging PET's view of P3). It resolves the contradiction by arguing that premise 3, based on a surface reading, misinterprets the nature and context of the divine commands.

Through a rigorous analysis grounded in God's full character, specific covenantal contexts (Field), the stated justification for divine action (Basis), God's intended aim (Target), the nature of the commanded action (Mode), and the overarching redemptive plan (Telos), CVE argues that what God actually commanded was not "genocide" as understood in premise 4 (i.e., the intentional destruction of a people as such, constituting a moral atrocity).

Rather, CVE proposes that God, acting in His unique role as Sovereign Judge within a specific redemptive-historical moment, commanded severe acts of judgment aimed at specific, context-dependent divine Targets. Crucially, because God's character is perfectly good and holy, His intended Target must always be aimed at achieving a genuine good (e.g., executing justice against systemic, destructive wickedness defined as the Basis; preserving covenant faithfulness). This good divine Target must be carefully distinguished from the severe means (Mode) commanded and its often horrific, foreseen consequences within that specific context.

While involving violence and tragic consequences (potentially impacting entire communities due to the logic of corporate identity prevalent in the ancient Field), the divine command, properly understood through CVE's framework, differs significantly in its Basis (specific condemned practices vs. ethnicity) and intended divine Target from the modern concept of genocide assumed in premises 3 and 4 of Rauser’s theological dilemma.

Thus, CVE affirms C7 (Yahweh didn't order genocide-as-atrocity) without resorting to textual errancy. It offers a path that preserves both divine goodness and textual integrity by demanding a deeper, theologically informed interpretation of the commands themselves. This article will outline CVE's framework and demonstrate its capacity to address the challenge of biblical violence more effectively than Rauser’s PET.

Setting Aside Hyperbole (Sort Of): Its Relevance and Limits

Before diving into Rauser’s view, it's important to clarify the role of Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) literary conventions, including hyperbole, in understanding biblical violence. This is a point where my approach finds partial agreement with Rauser but ultimately diverges in its application. We both agree that simply identifying hyperbolic language in conquest narratives does not, by itself, fully resolve the profound moral questions these texts raise.

As Rauser rightly points out, even if the numbers were exaggerated or the commands weren't followed to the absolute letter, the texts still appear to depict divinely sanctioned violence that includes noncombatants, which remains deeply troubling. The core issue isn't just the scale but the nature of the commanded action.1

However, CVE argues that understanding these texts requires acknowledging ANE literary conventions like hyperbole as one crucial factor in interpreting what kind of action (Mode) was actually commanded or described. CVE, using terminology from Christine Swanton’s Target-Centered Virtue Ethics (TCVE), calls this the mode of action.2

ANE warfare accounts often employed highly stylized, exaggerated language to signify total victory, complete devotion of spoils or enemies to a deity (herem), or the political and religious supplanting of one group by another. Phrases like "leave nothing alive that breathes" or claims of annihilating entire populations often functioned as rhetorical declarations of ultimate triumph and divine judgment signaling the completeness and irreversibility of the intended outcome, rather than necessarily serving as precise, literal military orders or exhaustive reports.3

Recognizing this potential hyperbole (alongside other genre features and accommodation) in the description of the mode is crucial for CVE's analysis for several reasons:

- It Refines the Moral Question: Instead of necessarily evaluating a divine command for the literal, exhaustive slaughter of every individual, we might be evaluating a command for decisive judgment and removal of a corrupt system (Target), expressed using the intense, totalizing rhetoric conventional for signifying complete judgment in that historical and literary field. The moral evaluation shifts, though difficulty remains.

- It Interacts with Divine Intention (Target): Hyperbolic or stylized rhetoric often emphasizes the intended result or target (e.g., complete judgment against the Basis, elimination of idolatrous influence) more than demanding a specific, literal execution of every detail of the mode. CVE focuses on discerning God's underlying Target, rooted in His revealed character (Exodus 34:6-7) and covenant purposes (Telos), and evaluates the commanded mode (interpreted contextually, accounting for genre and potential accommodation) in light of that Target.

- It Contextualizes the Severity: Understanding the conventional nature of this rhetoric helps situate the commands within their proper ANE field, preventing us from imposing modern literalism anachronistically onto the description of the mode.

Therefore, while CVE concurs with Rauser that identifying hyperbole is not a complete solution—the texts still depict morally challenging divine commands involving brutal violence aimed at specific divine Targets—it views recognizing these literary conventions as an essential interpretive step for understanding the likely nature of the commanded or described mode. Clarifying the likely mode informs the subsequent moral analysis within CVE's broader framework.

CVE's full response goes beyond analyzing the rhetoric of the mode to engage the deeper questions of divine character, covenant context (Field), the specific Basis for judgment, the intended divine Target, the distinction between intention and foreseen consequences, and the overarching redemptive Telos, integrating insights from thinkers like Murphy, Swinburne, Adams, and Stump to offer a comprehensive framework. Understanding literary conventions like hyperbole is necessary groundwork for interpreting the mode, but the main ethical work lies in analyzing the command's justification and purpose (Target, Basis, Telos) within CVE's broader theological structure.

Now let’s turn to breaking down Rauser’s view on biblical violence.

Rauser’s Position on Biblical Violence

Rauser’s Four Arguments

In his article “Let Nothing that Breathes Remain Alive,” Rauser articulates four central arguments that form the backbone of his resolution of the theological dilemma. These arguments work collectively to dismantle the plausibility of Premise 3 while strongly affirming Premise 4, thus leading to the acceptance of Conclusion 7.

By way of outline, here’s what his arguments accomplish:

- Arguments 1 and 2: Serve primarily to solidify Premise 4 (Genocide is always a moral atrocity), making it non-negotiable.

- Argument 3: Directly attacks the justifications often used to defend Premise 3 (Yahweh ordered genocide), undermining its credibility.

- Argument 4 offers a practical, prudential reason to reject Premise 3.

Let's examine each argument.

Argument 1: Bludgeoned Babies (Supporting Premise 4)

Rauser argues forcefully that the intentional killing of children is an unqualified evil. Citing examples like the 1994 Rwandan genocide, he asserts that any person with properly functioning moral cognition instinctively condemns such acts. This conviction is captured in his Never Ever Bludgeon Babies (NEBB) principle, which he considers an indubitable moral truth known through intuition, akin to perceiving logical truths.

He uses an analogy with sense perception: just as one can see that a ball cannot be simultaneously red and blue all over, one can intuit the absolute wrongness of bludgeoning babies. This knowledge isn't based on ignorance of potential divine reasons but on positive moral perception. He challenges the consistency of those defending the Canaanite slaughter, asking if the horror of baby killing disappears simply by changing names and dates ("Hutu bludgeoner" to "Israelite bludgeoner," "Tutsi baby" to "Canaanite baby," 1994 to 1450 BC).4 Defending such acts requires overriding this fundamental moral certainty.

The upshot is that by establishing the absolute, intuitive wrongness of acts central to genocide (killing children), this argument makes Premise 4 undeniable. This intensifies the conflict with Premise 3 when considered alongside God's perfection (Premise 1).

Argument 2: Calley's Corruption (Supporting Premise 4)

Taking the issue further, Rauser argues that even if one tried to justify the killing itself, the act of carrying out genocide is inherently a moral atrocity due to the devastating psychological and spiritual damage it inflicts on the perpetrators. He points to the case of William Calley (My Lai massacre) and studies on PTSD in soldiers, showing war's corrupting potential. Carrying out the herem commands, he contends, would have similarly corrupted the Israelite soldiers. A command that necessitates such corruption cannot be from a perfectly good God.

This adds another layer to Premise 4, showing genocide is atrocious not only for victims but also for perpetrators. It makes the idea of a perfect God issuing such a command (Premise 3) even more problematic, strengthening the impetus to reject Premise 3.

Argument 3: Rationalizing Genocide (Attacking Premise 3)

This argument leverages Noam Chomsky's principle of universality (applying the same moral standards to ourselves as to others). Rauser argues defenders of the Canaanite conquest violate this by carving out an extraordinary exception for Israel through rationalization.

He identifies a common pattern: "divide, demonize, destroy." An in-group (Israelites) claims superiority/divine sanction, demonizes the out-group (Canaanites) as a threat, and justifies their destruction – a pattern mirroring justifications for modern genocides (Nazi, Hutu). He highlights inconsistencies, like condemning Canaanite child sacrifice while endorsing a broader slaughter, as evidence of special pleading. Such rationalizations are needed precisely because the command itself (Premise 3) doesn't align with universal moral standards or divine consistency.

This argument directly undermines the perceived legitimacy and justifications for Premise 3. By exposing the problematic reasoning required to defend it, Rauser weakens its standing as a credible divine command, making its rejection more plausible.

Argument 4: The Cost of Genocide (Prudential Reason to Reject Premise 3)

Rauser presents a pragmatic argument: the belief that God commanded genocide (affirming Premise 3) has historically fueled horrific violence, with Christians citing the Canaanite narrative to justify atrocities (e.g., Carolingian massacre of Saxons). Rejecting this interpretation—denying Premise 3—removes a dangerous ideological precedent. The negative practical consequences of affirming Premise 3 provide a compelling reason to seek interpretations that avoid it, such as concluding Premise 3 is based on textual error.

This offers a practical, moral incentive to reject Premise 3. The devastating historical impact of believing it true makes denying it a more ethically responsible choice, supporting Rauser's resolution.

Rejecting Premise 3

Rauser's four arguments converge to support his resolution: maintaining God's perfection (Premise 1) and the absolute wrongness of genocide (Premise 4) requires rejecting the claim that God actually commanded it (Premise 3). Arguments 1 and 2 solidify the moral horror, Argument 3 dismantles the justifications for the command, and Argument 4 highlights the dangerous consequences of accepting it. For Rauser, this leads to the conclusion that Premise 3 reflects an error within the biblical text, not a factual report of a divine command, thus preserving both God's goodness and our core moral intuitions (Conclusion 7).

From Rauser's Article to His Book: Setting the Stage

At the end of his article, after presenting the four arguments against God commanding genocide, Rauser writes:

"While this may not yet tell us how we should respond to biblical narratives of divinely sanctioned violence, at the very least it will save Christians from the sorry spectacle of attempting to convince ourselves and others of that which everybody knows cannot be true." (2009: 41)

The specifics of how to respond are detailed in his book, Jesus Loves Canaanites. Before going into alternative theories or critiques of Rauser's arguments, it's helpful to understand his full framework. Assuming, for the sake of argument, that Rauser's four arguments successfully show Yahweh did not order genocide as commonly understood, a key question arises: Why would Scripture, inspired by a divine author, include narratives that seem to attribute such commands to God?

Rauser's Five Principles for Interpreting Scripture

In chapter 7 of Jesus Loves Canaanites, Rauser outlines five guiding principles for reading Scripture. These principles form his interpretive methodology and shape his approach to challenging texts like the conquest narratives.

Principle 1: The Perfect God

This principle anchors Rauser's approach in the nature of God, echoing step 1 in the logical argument from his paper: God is the most perfect being conceivable, possessing all perfections, including omniscience, moral perfection, and omnipotence. How does this relate to biblical inspiration? Rauser, referencing William Lane Craig, uses the concept of middle knowledge:

"Because God omnisciently possesses perfect middle knowledge (i.e. knowledge of counterfactual possibilities) he can orchestrate the conditions in which human creatures will freely write the precise words that he desires in his canon. Once those words have been written, God appropriates them into his canon by making their words his words." (2021: 133)

On this view, Scripture results from divine intent and aligns with God's purposes. When encountering texts attributing apparent immorality to God, His moral perfection dictates three possibilities for Rauser:

"1. The text is in error; 2. My understanding of the text is in error; 3. My understanding of moral perfection is in error." (2021: 33-34)

The Perfect God principle implies that apparent flaws might serve a purpose intended by the divine author, prompting careful rereading. But what if careful reading suggests the text itself is in error (option 1)? How can a text overseen by a perfect God contain errors? Rauser clarifies that biblical inerrancy, in his view, applies primarily to:

"the intentions of the perfect God who oversees the composition and compilation of the entire text: if God is the perfect author then at least with respect to God's intentions there will be no errors or goofs in the text. God, after all, knows perfectly well what he wants to say. But that divine intention may not always be available to the human author." (2021: 140)

This distinction leads directly to the next principle.

Principle 2: Two Authors (Human and Divine)

Rauser addresses potential textual errors by emphasizing Scripture's dual authorship: human and divine. Crucially, the intentions of these two authors can diverge. The human author might not grasp or convey the divine author's full intent. This involves two senses of meaning: the literal sense (human author's intent) and the plenary sense (divine author's intent), which may differ.

He illustrates this using Isaiah 7:14 ("Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign: The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel"). Rauser suggests the literal sense is related to a sign for King Ahaz involving a young woman's child, while the plenary sense points prophetically to the virgin conception of Christ.

The significance of the Two Authors principle is:

"Since I believe God is not merely a great author but the one perfect author, I am committed to the reading assumption that God did not commit any errors in the plenary sense even if God inerrantly included human errors in the literal sense." (2021: 145-46)

Therefore, even if the literal sense seems to portray God commanding genocide (which Rauser rejects based on his four arguments), this doesn't bind the divine meaning (plenary sense) to that immoral portrayal. One can trust the perfect divine author intends a meaning consistent with His character, even if it requires looking beyond the human author's literal expression.

Principle 3: The Canon as a Unified Whole

This principle views Scripture as a unified revelation crafted by God. Every part is intentionally included and serves the whole narrative. Therefore, individual passages must be interpreted in light of the entire canon. Isolating texts risks misinterpreting their meaning within the larger divine message.

Rauser advocates using "control texts"—key passages that illuminate dominant themes throughout Scripture—to guide interpretation. While he doesn't provide strict rules for identifying these, he emphasizes God's perfection and moral intuition as vital guides, especially when dealing with biblical violence.

Principle 4: Jesus as the Supreme Revelation

Jesus Christ represents the ultimate revelation of God's character. Rauser states, "the life and teachings of Jesus provide the final guide for all interpretation and application," (2021: 153) fundamentally shaping how Christians should approach difficult texts depicting divine violence.

He contrasts two approaches: viewing Jesus' work as continuous with and completing Old Testament violence, versus seeing Jesus' life and teachings as a radical critique and in discontinuity with that violence. Rauser adopts the latter, suggesting New Testament revelation should inform our understanding of Old Testament difficulties.

For Rauser, Jesus' life and teachings are the ultimate control texts. This isn't about creating a smaller "canon within the canon," but rather:

"it is a commitment to the belief that the sum total, fullness and completion of God's revelation comes in Jesus Christ such that the whole of scripture should be read in light of him." (2021: 156)

Jesus' emphasis on loving neighbors and enemies becomes ultimate. Any interpretation that promotes alienation, demonization, or harm contradicts this central revelation.

Principle 5: The Goal of Love

Scripture's ultimate purpose, according to 2 Timothy 3:14–17, is salvation through faith in Christ and training in righteousness, culminating in love for God and neighbor (Luke 10:27–28). Therefore, any interpretation that hinders this goal of love must be incorrect, even if it seems textually plausible. Rauser puts it passionately:

"If that is what scripture is for, if it is for the end of conforming us into the image of Jesus so that we may love all people, including outsiders, the others, the outgroup, the wayfarer, stranger and enemy, if it reaches out to and encompasses both Samaritans as well as Canaanites, and if it calls us to love all these people as we love ourselves, then any reading which is inconsistent with that ethical, spiritual goal cannot be correct and it needs to be rejected....[I]f our current way of reading portions of Scripture is not creating greater lovers of God and/or neighbor, if it instead leads us to objectify and dehumanize our neighbor as when theologians like Archer demonize Canaanites as a 'cancer of moral depravity' and 'baneful infection,' then we need to return to the text and seek a new interpretation because that reading cannot be right. No reading that reduces our neighbor to being a disease can be a correct reading." (2021: 160)

Drawing on Eric Seibert, Rauser concludes that correct interpretations foster love and do not inspire, promote, or justify violence, oppression, or harm. An interpretation is sound when it leads readers toward greater love for God and neighbor.

Rauser's Engagement with Alternative Views on Biblical Violence

To better understand Rauser's position, it's helpful to briefly examine his critique of other common interpretations of biblical violence.4 Seeing why Rauser rejects alternative paths clarifies the rationale behind his own theory.

Critique 1: The "Genocide Apologists"

Rauser uses this direct label, acknowledging that many within this group might resist it. However, he argues the label fits because they implicitly or explicitly accept two claims: 1) God genuinely issued commands that align with the 1948 UN definition of genocide, and 2) Since God is a morally perfect law-giver, these commands were morally permissible, even obligatory.

Historically, John Calvin represents this view: God holds the prerogative over life and death, and His commands are inherently just and right, even if similar actions would be immoral outside divine authority. Calvin points to God's mercy (waiting 400 years) and the Canaanites' alleged extreme moral depravity as justifications for their total destruction, including children.5

Contemporary examples include Clay Jones (2009), who meticulously lists Canaanite sins warranting destruction, suggesting that reluctance to accept God's commands stems from not taking sin as seriously as God does.

Rauser criticizes this group for special pleading and rationalization. He argues they fail to confront the horrific reality of close-quarters mass killing and overlook the brutalizing effect such warfare would have on the perpetrators. He warns this view can desensitize adherents, leading them to see violence as pious work, potentially even enjoying the eradication of perceived "cancers."

What about the common defense that the herem was necessary to protect Israelite fidelity? Rauser counters using his Perfect God principle. He finds the claim that slaughter was the only way an omnipotent God could protect Israel from Canaanite influence deeply problematic:

"would entail that the only way an omnipotent God could protect the Israelites from the sin of the Canaanites was by way of slaughtering the whole society or something worse. Really?...To suggest that this was the least grisly avenue open to an omnipotent being who wished to secure the moral purity of the Israelites is to strain credulity well past the breaking point." (2021: 181)

An all-powerful God had countless other options, from miraculous intervention to natural displacement. Furthermore, this apologetic conflicts with the Jesus and Love principles. Jesus taught universal love, making the exclusion of Canaanites problematic. This view also requires dehumanizing the victims to justify their slaughter, directly opposing the call to embrace the outcast.

Critique 2: The "Just War" Interpreters

This group resembles the apologists in affirming the commands as historical divine orders but explicitly rejects the "genocide" label. They argue God sometimes uses warfare in unique, unrepeatable circumstances for judgment, and the Canaanite conquest aligns with just war principles.

Rauser engages with Justin Taylor, who argues the destruction wasn't genocide because exceptions were made for repentant individuals (Rahab, Gibeonites), indicating the targeting wasn't based purely on ethnicity but on rebellion against God.6

Rauser counters that the texts clearly target Canaanites as a distinct group marked by specific religious practices considered abhorrent. He states, "That desire to kill distinct Canaanite religious identity and practice is all that is required to classify the actions undertaken by the Israelites as genocidal" (2021: 195). The sparing of shrewd individuals like Rahab or the Gibeonites doesn't negate the overall goal of eliminating the group's religious identity.

He then addresses key Just War proponents Paul Copan and Matthew Flannagan (Did God Really Command Genocide?). They argue:

- The primary command was to drive out the Canaanites, like a landlord evicting tenants, not primarily to kill them.

- Cities like Jericho and Ai were primarily military forts (following Richard Hess), not large civilian centers, minimizing noncombatant deaths.

- The language describing total destruction is hyperbolic, signifying decisive military victory, not literal annihilation. Claims of such victory are also hyperbolic.

Rauser responds that even a "drive out" scenario constitutes ethnic cleansing. Furthermore, it likely involved slaughtering the most vulnerable (elderly, disabled, young children) who couldn't flee quickly. He graphically imagines this outcome to counter attempts to sanitize the violence:

"[W]hat would happen to those people, the least of these of Canaanite society, upon meeting the advancing Israelite soldiers. The answer is clear: anyone who remained behind would be slaughtered with sword and spear and whatever bludgeoning tools may lie about...the Israelite soldiers would turn themselves upon the victims in a pious religious frenzy, plunging their spears into the abdomens of squirming toddlers, hurling large rocks down on the skulls of crawling disabled adults, swinging their swords into the necks of shivering elderly women." (2021: 203)

Military forts invariably house noncombatants. Joshua 8:25 explicitly mentions "Twelve thousand men and women" killed at Ai. Claiming no noncombatants were killed strains credibility. Further, hyperbole doesn't negate intent. Even if numbers were exaggerated, the texts still appear to describe an intent to destroy the religious-ethnic group as such. Reduced numbers or survivors don't change the fundamental moral problem of the command's apparent goal.

Critique 3: The "Spiritualizers"

This approach interprets violent passages allegorically. For example, Psalm 137:9 ("Happy is the one who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks") isn't taken literally but, following C.S. Lewis, as representing the "killing" of sinful desires before they mature.7

Rauser points to Origen's allegorical reading of the fall of Jericho (Joshua 6:16-17), where the command to destroy everything in the city becomes an injunction against bringing worldly ways into the Church.8 Modern scholars like Douglas Earl similarly interpret Canaanites not as literal people but as symbols of sinful impulses.9

Rauser raises three objections:

- Symbolic interpretation doesn't necessarily resolve the moral problem if the text also refers to literal events.

- Spiritualizers face a dilemma: Did the events happen historically? If yes, allegory distracts from real-world violence. If no, biblical history becomes useful fiction, potentially undermining trust in Scripture's reliability.

- Allegorical interpretation often lacks clear controls, risking subjective eisegesis (reading meanings into the text).

Despite these criticisms, Rauser acknowledges valuable insights from "New Spiritualizers":

- Herem relates to covenant fidelity in hostile territory, focusing on spiritual survival more than just physical battle.

- The phrase "the battle is the Lord's" should prevent these texts from licensing human violence in God's name.

- Herem highlights boundary dynamics: outsiders (Rahab, Gibeonites) can be included, and insiders (Achan) excluded, calling for humility. (2009: 271)

However, Rauser finds this insufficient. He believes the sheer ugliness of the literal text demands condemnation; simply spiritualizing it away doesn't align with the Jesus and Love principles. Only by acknowledging the literal sense as depicting something morally wrong (an error) can one read faithfully.

Rauser's Position: Providential Errantism

Rauser aligns himself with Providential Errantism. This view holds that the conquest narratives contain moral errors—specifically, misrepresentations of God's character and commands—which God nevertheless providentially allowed and included in Scripture for pedagogical purposes. Echoing Greg Boyd, Rauser suggests God inspired the overall text but permitted human authors' flawed moral perspectives, using these errant inclusions to provoke readers toward deeper moral discernment and wrestling with the text.10

This solution aims to preserve God's moral perfection (by denying He commanded genocide) while upholding a form of inspiration (God intentionally used flawed human accounts for our growth). Rauser grounds this in two concepts:

- Progressive Revelation: God reveals truths gradually over time. Jesus, in fulfilling the Law, also corrected misunderstandings of it.

- Accommodation: God meets limited, flawed humans where they are to guide them toward deeper understanding. Rauser cites L. Daniel Hawk: "God had to enter and identify with a violent world in order to establish the basic understanding of human dignity that would form the foundations for more refined ethical sensibilities." (2021: 283)

Rauser distinguishes his view from the idea that God actually commanded genocide as an accommodation to ANE violence. He finds that incompatible with God's perfection, asking why an omnipotent God couldn't reveal His will without endorsing genocidal practices, especially when Jesus later directly challenged flawed moral assumptions. Such accommodation might also seem to license other immoralities.

Instead, Rauser favors the interpretation where God allowed the Israelites to falsely believe He commanded genocide. Why? As part of a divine pedagogy, forcing readers to "critically engage with them, confident that they are included to form the faithful reader into a lover of God and neighbor." (2021: 296).

He incorporates Greg Boyd's analogy of these texts as "literary crucifixes," where God bears the sin of His people—including their sinful portrayal of Him as a genocidal warrior—taking on a literary appearance reflecting that sin, demonstrating His willingness to stoop into their flawed understanding.

While Boyd tries to retain some historicity (suggesting Israel distorted God's nonviolent Plan A into violence), Rauser remains critical, noting even Boyd's Plan A (driving Canaanites out with hornets) involves violence and ethnic cleansing.

Endorsing Eric Seibert's call to "read with the Canaanites" (humanizing them as God's image-bearers), Rauser addresses the resulting textual ambiguity. Why didn't God make His disapproval clearer? He flips the question:

"Rather than focus only on the question of whether God has done enough to disambiguate the Bible, perhaps we should ask: have we? It could be that one important reason that God has allowed the degree of ambiguity that exists is precisely so the church can undertake the responsibility of faithful pastoral and community disambiguation of the text. Perhaps there is intrinsic value in the church as a corporate body wrestling with Scripture in this manner as Jacob wrestled with the angel." (2021: 329)

Ultimately, Rauser argues, faithfully wrestling with these difficult texts, guided by God's perfect character revealed in Christ and the call to universal love, leads to recognizing the problematic commands as human error providentially included, not as direct divine mandates.

Moral Intuition

The final piece of the puzzle to Rauser's view of biblical violence is his reliance on moral intuition. He is a moral realist who thinks our conscience can give us immediate, non-inferential starting points for moral evaluation. As mentioned earlier, he thinks we have a moral faculty akin to our perceptual faculty that can reliably deliver beliefs that form the bedrock of our theorizing. Any person with a properly functioning cognitive capacity should be able to see that commanding genocide is inherently evil.

Regarding moral intuitions and the Canaanites, Rauser wonders if one's conscience:

"might also justify one in rejecting the claim of a historic, divinely commanded genocide a priori? Can our intuitions bar the door to consideration of the claim that the perfect God of absolute love commanded the mass slaughter of an entire society: not just male combatants, but also women, children, infants, the mentally handicapped, and the elderly?" (2021: 73)

Rauser follows Budziszewski in claiming that killing innocent humans is intrinsically wrong. But, here's where things get especially problematic. Moral intuitions dictate how we must read the Bible. If one's intuition tells against God commanding a genocide in history, then

"whatever the biblical texts may mean to teach us, they cannot intend to teach us that. And insofar as your conscience likewise forbids the idea that God commanded such apparent moral atrocities, you ought not to believe it." (2021: 75).

As might be apparent, Rauser places significant weight on our God-given moral intuitions. He argues that our intuition strongly recoils at the idea of a loving God commanding the slaughter of infants and non-combatants. This intuition, while fallible (like hermeneutics), is a crucial guide. In his debate with Paul Copan, he asks pointedly if we can imagine Jesus guiding a soldier's spear into a child.

Problems with Intuition-Driven Inquiry

Now that we have a picture of Rauser's view on biblical violence, it's time to turn to the critical task. First, it's good to acknowledge the intuitive appeal of Rauser's position. No one wants to believe God commanded moral atrocities. His view entails that God didn't. That's a positive and satisfying result on many levels. Yet, there are serious problems just under the surface of this rosy picture. Let's work backwards through his view, starting with what we just discussed--his privileging of moral intuition as a gatekeeper for admissible readings of Scripture.

There are many potential problems with elevating moral intuition as Rauser does when it comes to trying to interpret and make sense of biblical violence. The issues fall into three categories: theological, moral, and philosophical.

Theological Problems

The first group of concerns focus on Rauser's view undermining divine authority and revelation. His approach risks placing fallible human intuition (even if God-given) as a higher authority than divine revelation (Scripture). Traditionally, theology holds that Scripture judges human intuition, not the other way around. If our intuition determines what Scripture can mean a priori, then revelation is effectively limited by human sensibilities.

Regarding God's sovereignty and inscrutability, Rauser's view potentially limits God's ability to act or command in ways that transcend or challenge human understanding. God's reasons might be inscrutable or part of a larger plan not immediately obvious to our moral sense (cf. Job, Romans 9). Dismissing interpretations a priori prevents grappling with the possibility of divine purposes beyond our immediate grasp. This is especially problematic given Rauser's emphasis on "wrestling with Scripture...as Jacob wrestled with the angel." Writing off interpretations because they conflict with intuition forfeits this deeper search for the ways of God.

When it comes to the nature of sin, Christian theology often emphasizes the noetic effects of sin. It damages our cognition in crucial ways. The Fall corrupted all human faculties, including reason and moral intuition. Although this doesn't make intuition useless, it means it's fallible, potentially biased, darkened, and not always a reliable guide to moral truth. Relying on it as the ultimate arbiter ignores its potential corruption. Can we confidently assert our post-Fall intuition perfectly mirrors God's moral commitments? Though our faculty of intuition may be God-given, it is still marred by the ravages of sin.

Additionally, there are issues concerning progressive revelation and challenging norms. God often challenged the existing moral and religious norms of His people throughout Scripture (e.g., Peter's vision about unclean foods, Jesus' reinterpretation of the Law). If prior intuition had been the absolute standard, such revelations might have been rejected a priori. This approach risks freezing revelation at the level of current human intuition.

There's also the worry that heavy reliance on moral intuition results in us creating God in our own image. There's a danger of tailoring our understanding of God to fit our moral comfort zones, rather than allowing Scripture, even its difficult parts like the conquest narratives, to shape and potentially correct our understanding of God. It risks fashioning a God who always conforms to contemporary Western liberal sensibilities, rather than the potentially more complex and challenging God revealed in the whole counsel of Scripture.

Moral Problems

The next set of concerns focus on moral issues. First we have worries concerning subjectivity and relativism. Moral intuitions vary significantly across cultures, historical periods, and even individuals. Whose intuition becomes the standard for biblical interpretation? Rauser might appeal to a "properly functioning" intuition, but defining that without circularity (i.e., it's properly functioning if it agrees with my view) is difficult.

There's also a great deal of historical variance. Past societies had radically different moral intuitions about things like slavery, honor killings, or the status of women. Using our specific historical moment's intuition as the absolute judge of ancient texts seems chronocentric and potentially arrogant.

Conflicting intuitions is also an issue. Rauser allows that intuitions can be person-relative. And, even today, people have conflicting intuitions on major moral issues (e.g., abortion, euthanasia, economic justice). How does this method resolve interpretive disputes when intuitions clash? It risks leading to interpretive anarchy based on subjective feelings.

The next group of worries center around oversimplification of complex issues. There's a neglect of context built into moral intuition. It often operates on simplified scenarios ("killing babies is wrong"). It may struggle to adequately process the unique, complex historical, theological, and covenantal contexts presented in passages like the Canaanite conquest. It may neglect the conquest as a unique historical moment, questions of corporate identity/judgment, and potential unique divine purposes. Intuition might offer a strong negative reaction without fully engaging the specific claims and context of the text.

Additionally, intuition struggles with something regularly dismissed, namely that God as the creator and sustainer of all life has a unique prerogative with regard to life. While killing innocents is intuitively wrong for humans, the theological question involves whether God, as the author of life and ultimate judge, might operate under different moral parameters or have morally sufficient reasons (even if unknown to us) for commanding actions that would be wrong for humans to initiate. Intuition struggles with such potential divine prerogatives.

Lastly, intuitions can be strongly influenced by emotion. Rauser sees this as a good thing. We should be morally disturbed, if not outraged, by the thought of God commanding the killing of innocent persons. This runs the risk of self-deception. One thinks intuition is reliably tracking the moral facts and the emotions are simply amplifying the objective moral valence, but in reality cultural conditioning and personal desires can impact intuitive responses to troubling texts. You might intuitively reject a difficult doctrine not because it's truly immoral, but because it's uncomfortable or challenges one's preferred view of God or oneself.

Philosophical/Epistemological Problems

The last set of concerns with Rauser's intuition-driven critique of Scripture are philosophical. More specifically, they impact moral intuition as a source of moral knowledge. I'll keep this section brief, but you should know there are deep philosophical waters concerning the reliability of moral intuition and intuition generally.

Concerning their reliability, intuitions are susceptible to numerous cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias, framing effects, and emotional reasoning. While Rauser likens it to perception, moral intuition lacks the same kind of external verifiability and corrigibility as sensory perception. We can test if our eyes deceive us, but testing the "accuracy" of a moral intuition against objective reality is far more complex.

As hinted at earlier, relying heavily on personal intuition when interpreting texts can lead to a logical fallacy known as circular reasoning or question-begging. This occurs when the conclusion you reach is already assumed in your starting point. For example, someone might follow this line of thought: "My gut feeling tells me that commanding genocide is profoundly immoral. Because I believe God is perfectly moral, God could never command such a thing. Therefore, any religious text that appears to show God commanding genocide cannot mean what it seems to say and must be interpreted differently." The problem here is that the final interpretation of the text isn't derived from analyzing the text itself, but is instead dictated by the initial intuitive judgment about morality and God's nature; the conclusion is effectively "baked into" the premise.

Regarding epistemology, there's the problem of foundationalism. Rauser seems to treat these moral intuitions as properly basic or foundational beliefs. However, it's debatable whether complex moral judgments like "God commanding group killing is intrinsically wrong" are truly foundational, or if they are derived from other beliefs (about God, justice, human value, etc.), which themselves might need grounding or could be challenged by revelation.

Also, there are issues concerning falsifiability. If interpretations are dismissed a priori based on intuition, it makes certain theological claims effectively unfalsifiable or immune to textual evidence. How could Scripture ever genuinely challenge or correct our deeply held moral assumptions if those assumptions are used to preemptively filter Scripture's possible meanings?

There are also scope limitations. Basic moral intuitions (e.g., against wanton cruelty) might be reliable starting points, but it's a significant leap to claim they have the precision and scope to definitively adjudicate complex, context-specific, historical-theological questions about alleged divine commands within ancient texts.

Summary of Issues Regarding Moral Inquiry

In sum, though Randal Rauser's concern for reconciling Scripture with a morally pure God is commendable and resonates with many, grounding biblical interpretation primarily on the veto power of current moral intuition presents significant theological, moral, and philosophical difficulties. It risks subjectivism, undermines the authority of revelation, potentially ignores the complexities of sin's effects on human faculties, and may prematurely close off engagement with the challenging aspects of the biblical text and the nature of God Himself.

A more traditional approach would argue for a dialectic where intuition informs interpretation, but Scripture ultimately holds the corrective authority, even when it deeply challenges our sensibilities. And, a competing approach to intuition driving moral inquiry is to have theory driving moral inquiry. On such a model you start with a moral theory and you allow that theory to shape interpretations of Scripture and revise moral intuitions. This is the approach I will take in a bit.

Objections to Rauser's Overall View

Rauser embraces Providential Errancy. This means there's a difference between what the report says God commanded and what God actually willed. Rauser's view supports this by attributing the "error" in the report to the human author's flawed perspective, which God providentially allowed for pedagogical reasons, while God's "actual will" aligns with Jesus/love.

Rauser's combination of intuition-driven inquiry, his five principles for Biblical interpretation, and his embrace of Providential Errancy generates many worries. Below are four such worries formulated as objections.

The Objection from Epistemic Circularity

Can Rauser’s method reliably establish God's "actual will" to contrast it with the report of God’s will, one which contains errors?

The Objection from Epistemic Circularity, as I call it, challenges the very possibility of the method working reliably. For Rauser, "the life and teachings of Jesus provide the final guide for all interpretation and application," (2021: 153), and this fundamentally shapes how Christians should approach difficult texts depicting divine violence.

For Rauser, Jesus' life and teachings are the ultimate control texts. They are the ultimate filter for interpretation, and this "is a commitment to the belief that the sum total, fullness and completion of God's revelation comes in Jesus Christ such that the whole of scripture should be read in light of him" (2021: 156).

Jesus' emphasis on loving neighbors and enemies becomes ultimate. Any interpretation that promotes alienation, demonization, or harm contradicts this central revelation and should be rejected. But, this creates a problematic form of circularity regarding knowing God’s actual will from the mere reports of his will (which may be in error).

Here's the problem:

- We need to use Jesus (our Tool) to check Scripture for errors.

- But we get our knowledge of Jesus (the Tool) from Scripture itself.

- If Scripture can contain errors, how do we know for sure that the specific parts telling us about Jesus are completely free from error? What if those parts are also influenced by flawed human perspectives?

- To confidently use Jesus as the perfect, error-free standard, we must first trust that the scriptural accounts about Him are perfectly reliable representations of God's actual will.

- BUT...the method starts by saying Scripture might contain errors. If we just assume the Gospel parts about Jesus are error-free without an independent reason, we are essentially assuming part of our conclusion (i.e., "these specific parts are reliable") before we even start.

The question for Ranal to address are: How does your method avoid problematic circularity? What’s the justification for trusting the source of the standard, given the view's own admission about the potential fallibility within that source?

Without a good answer, it looks like the method relies on assuming what it needs to prove: that the scriptural basis for its standard is reliable.

Intuition to the Rescue? (No!)

Could an appeal to moral intuition break the epistemic circle?

Rauser relies on moral intuition to identify problems. This is the idea that interpretations conflicting with Jesus's life and teaching (which embody love) are incorrect, and that we should "condemn the moral errors" apparently commanded in some texts.

Could this same intuition be used to ground the standard? The argument might be: We intuitively recognize the supreme moral goodness and authority in the Gospel portrayal of Jesus, and that intuition validates Him as the true standard, independent of the logical loop.

This move faces significant challenges. Whose intuition counts? Are moral intuitions not heavily influenced by culture? My next objection suggests they are. Do all people share the same intuition about the Gospel portrayal? Definitely not.

Thus, relying on moral seemings to establish the fundamental standard seems more problematic than using it just to flag inconsistencies, as it risks making the foundation entirely subjective, as I argue in another objection. It likely doesn't offer a robust escape from circularity concerns for those demanding a more objective grounding.

The Objection from Imbalanced Moral Value Projection

Drawing on concepts from moral psychology, specifically Jonathan Haidt and Craig Joseph's Moral Foundations Theory,12 my worry is that Rauser’s approach engages in a form of moral projection. It imposes an imbalanced or culturally specific set of moral values onto the biblical text and its context, which leads to an uncharitable or inaccurate evaluation.

This objection focuses on the standard or lens being used to identify a "theological or moral error" in the biblical report when compared to God's "actual will." Rauser’s view implicitly uses a modern, Western-biased moral framework focused heavily on Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity to judge the ancient texts.13

Harm/Care and Fairness/Reciprocity are often emphasized in modern Western ethical discussions. When Old Testament texts depict actions causing harm (death, displacement) or appearing unfair (collective punishment, preferential treatment of Israel), they are flagged as morally problematic based on these foundations.

This neglects other moral values that are important within an Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) context. Such a context operated with a broader set of moral foundations, including (using Haidt and Joseph's categories):

- Loyalty/Betrayal (Ingroup): Concepts like covenant faithfulness, treason against God (idolatry), national solidarity, and distinctions between insiders and outsiders were paramount.

- Authority/Subversion: Respect for divine authority, the legitimacy of God's commands (even harsh ones), social order, and judgment against rebellion were crucial.

- Sanctity/Degradation (Purity): Ideas about holiness, ritual purity, avoiding defilement (especially through idolatry or forbidden practices), and consecrating land or people were central.

To understand and evaluate the portrayal of God's character and actions in the Old Testament charitably and accurately, you need consider this broader set of moral values that were operative in that context. Judging solely by Harm/Fairness involves projecting a limited, potentially anachronistic, framework on that context.

The upshot is that evaluating God's actions (e.g., commanding conquest, enforcing purity laws, demanding exclusive loyalty) only through the lens of Harm/Fairness makes them almost inevitably appear as "moral errors." However, if you also consider the high value placed on Loyalty (to the covenant), Authority (God's sovereignty), and Sanctity (eliminating idolatrous defilement) within that cultural perspective, the rationale behind these actions within the text's own framework appears different, even if still challenging to modern readers.

Rauser’s method doesn't just identify conflicts with the ultimate revelation in Christ, but misinterprets the Old Testament context itself by failing to engage with its own complex moral landscape. It condemns commands and actions based on a selective application of moral values, rather than first seeking to understand those actions within the full spectrum of values presented or assumed by the text.

Before imposing a potentially narrow modern ethical grid onto ancient texts, and labeling something a "human moral error," you should strive to understand if it aligns with other moral values (like Loyalty, Authority, Sanctity) that were highly prized in that context and are arguably part of the biblical portrayal of God's concerns, even if those values sometimes lead to actions that conflict with modern Harm/Fairness priorities.

If the commands in the reports can be seen as coherent expressions of God's will concerning Loyalty, Authority, or Sanctity (attributes arguably part of God's multifaceted character, even if expressed harshly in that context), then they might not actually be "errors" relative to God's will as expressed then. And Rauser might be misidentifying contextual expressions of God's justice, holiness, or faithfulness as "errors" simply because they don't align with a modern, limited focus on harm and fairness.

The Impoverished Character, Impoverished Love Objection

Rauser’s view risks reducing God's morally perfect character primarily or solely to love, as emphasized by Jesus's command to love God and neighbor. This is problematic.

Such a reduction presents an imbalanced view of Jesus. While Jesus certainly emphasized love, his character and teachings also profoundly reflected God's holiness (opposition to sin), righteousness (upholding God's standards), faithfulness (to God's plan and promises), and justice (teachings on judgment, accountability). Focusing predominantly on love, particularly a concept of love seen as incompatible with judgment or severity, presents an incomplete picture of Jesus himself.

This leads to an oversimplified hermeneutical filter: "If it doesn't look like [this narrow conception of] love, it cannot be truly from God." This fosters misinterpreting the Old Testament. Applying this filter to challenging Old Testament passages like the conquest narratives leads to the conclusion that they cannot reflect God's true character because they involve violence and judgment, which are deemed "unloving." Consequently, they are dismissed as merely human "erroneous projections... of tribal war culture and mindset."

Reduction of moral perfection to love ignores other divine attributes in the OT. It overlooks how these same OT narratives can be understood as expressions of other facets of God's perfect moral character, operating within a specific redemptive-historical context:

- Faithfulness: God acting faithfully to His covenant promises to Israel (e.g., the promise of land).

- Justice/Righteousness: God enacting judgment against actions the text portrays as deeply sinful and persistent ("long condemned egregious sin"), upholding His righteous standards.

- Holiness: God preserving the holiness of His people or the land by opposing defiling practices (as understood in that context).

Cutting against this is the idea that God's character is consistent (holy, just, faithful, loving, etc.), but the expression of these attributes varies depending on the specific situation and the stage in redemptive history. The conquest narratives, in this view, show attributes like justice, faithfulness, and holiness being expressed in ways appropriate to that specific harsh context, even if this differs from how they are expressed in the person and work of Jesus in the New Covenant context.

Further, borrowing from previous objections, the reduction of God's character to love is problematic because the definition of love being employed is itself narrowly defined by Harm/Fairness concerns. This makes it almost inevitable that OT passages depicting God acting forcefully to uphold covenant loyalty, execute judgment (Authority), or eradicate perceived spiritual contagion (Sanctity/Purity) will be deemed "unloving" and thus dismissed as human error reflecting "tribal war culture," rather than being grappled with as complex expressions of God's multifaceted character within a specific, challenging historical context.

Thus, the concern is that by using an imbalanced view of Jesus (emphasizing only love) to create a simple "love filter," the approach fails to recognize the multifaceted nature of God's perfection and how attributes like justice, holiness, and faithfulness were also operative and revealed in the Old Testament, as contextually expressed. It risks discarding parts of scripture not because they truly contradict God's character, but because they contradict a reductionist understanding of that character.

The Objection from Harmful Consequences

This objection is that, on Rauser’s account, God lacks sufficient moral reason to allow errors due to the resulting harm they can cause.

For Rauser, God, despite being morally perfect and providentially meticulous, intentionally and providentially allowed human authors to include their own flawed perspectives and "gross moral errors" (like apparent divine commands for genocide) within the text of Scripture. God did this for a specific pedagogical purpose: to make readers wrestle with the text, recognize the human error through the lens of Christ, and ultimately learn deeper spiritual lessons about love and God's true character.

Yet, these reasons are morally insufficient given the severe negative consequences. A morally perfect and omniscient God would have foreseen that allowing such texts (even as human error) would:

- Cause believers profound doubt about His goodness.

- Lead some to lose faith or trust.

- Create deep moral confusion about His character.

- Be misinterpreted and misused historically to justify real-world atrocities (by people taking the human error as divine command).

Moreover, the supposed lessons Rauser claims God uses the error for are not widely recognized. So, not only are the benefits not sufficient to outweigh the harms, but God would have foreseen that most believers throughout the ages would have missed his ironic twist on the plain reading of the text within its ANE context. God would have foreseen that most would just be confused and not perform the necessary wrestling to grasp these deeper truths.

A morally perfect God wouldn't have morally sufficient reasons for allowing gross moral errors in the text that lead believers to question his goodness, lose faith, cause confusion, and inspire atrocities.

Thus, even if we grant the intention behind allowing these texts might be pedagogical, the reasons fail on two counts:

- Moral Justification: The pedagogical goals don't outweigh the harms, especially when less harmful methods would presumably be available to a perfect God.

- Practical Effectiveness: The method itself (embedding errors and relying on mystery) is a poor and potentially counterproductive way to achieve genuine clarity, sound critical analysis, and reliable character formation.

This highlights the negative consequences of adopting Rauser’s justification of providentially included errors. As a result, it directly challenges the coherence and moral weight of Rauser’s proposed divine rationale.

Given the cumulative worries and objections above, we’re warranted in considering a new way to interpret texts involving divine violence. Though I don’t think any of the critiques of Rauser’s view are knockdown arguments, they do cumulatively suggest the need for a better theory. To that I now humbly turn.11

Covenant Virtue Ethics: An Integrated Moral Theory

Philosophical Foundations and Purpose

Covenant Virtue Ethics (CVE) is a comprehensive normative ethical theory. It aims to articulate what makes actions right or wrong, define the nature of the good, and determine the basis of moral worth. Its main foundation lies in virtue ethics, specifically drawing significantly from Christine Swanton’s Target-Centered Virtue Ethics (TCVE). To this foundation, CVE adds crucial insights from Divine Command Theory (DCT) and Natural Law Theory (NLT), integrating them into a cohesive whole.

Unlike ethical systems that begin with human moral intuition or abstract philosophical reasoning, CVE takes its starting point as God's own self-revelation, particularly His character as shown within the context of covenant relationships described in Scripture. The description of God's character in Exodus 34:6-7 is considered the most pivotal expression of this self-revelation, displaying the rich tapestry of His perfect attributes, including both profound love and unwavering justice. As a result, CVE asserts that God's full revealed character, dynamically manifested within the framework of covenant, serves as the ultimate foundation and objective standard for all moral judgments.

Understanding and living out morality, therefore, involves discerning and reflecting God's perfect character. This is achieved through actions that successfully "hit the targets" defined by God's virtuous attributes. This is done while always considering the specific covenantal situation which constitutes the "field" (in TCVE terms) for moral action. The covenant is not merely a backdrop but the fundamental relational structure that establishes moral obligations and shapes the context in which virtues are properly exercised.

CVE is designed to satisfy both theoretical and practical ethical aims. On the theoretical level, it seeks to identify the essential features that render actions, persons, or states of affairs right or wrong, good or bad. CVE locates these moral properties in the successful expression of God's divine character. Such success consists in hitting the appropriate virtuous targets within the relevant covenantal context. On the practical level, CVE offers a structured decision-making procedure. This procedure guides agents toward correct moral verdicts by systematically integrating several layers of analysis: an assessment of the specific covenantal context (Field, Basis), character-based reasoning informed by TCVE's target analysis (Target), a careful analysis of intention utilizing principles like the Doctrine of Double Effect (DDE) to distinguish the intended aim from foreseen consequences of the chosen Mode, and an evaluation of how an action aligns with God's ultimate redemptive purpose (Telos).

Holiness, Authority, and the Metaphysical Size-Gap

God's relationship with creation, particularly with finite and morally imperfect beings like us, is shaped by His essential attribute of holiness. This holiness, revealed from the earliest encounters like the burning bush and the events at Sinai (Exodus 3:5; Exodus 19), and explicitly stated as foundational in the Law (Leviticus 11:44-45; 19:2), is central to who He is. It possesses a two-fold nature: it signifies His stunning majesty. This encompasses His absolute uniqueness, infinite power, self-sufficiency, and fundamental 'otherness' or separation from everything created (Exodus 15:11). Holiness also defines His perfect moral-purity. This is His absolute freedom from any taint of sin, evil, or defect, establishing Him as the ultimate, unwavering standard of righteousness and goodness. Without this essential holiness, God would cease to be God as He has revealed Himself.

Based on God’s holiness Christian philosopher Mark Murphy analyzes the implications of God's nature using concepts such as the "metaphysical size-gap" or the "absurd size gap," as Marylin McCord Adams also embraces. This term captures the immense, almost incomprehensible chasm, which is both ontological and qualitative, that exists between the infinitely perfect, absolutely holy, self-sufficient Creator and the finite, dependent, and morally deficient nature of created beings, particularly humanity after the fall. God's majesty-holiness establishes the staggering difference in being (infinite versus finite, uncreated versus created), while His moral-purity holiness establishes the stark contrast in character (absolute perfection versus sinfulness). This profound gap, rooted in God's absolute holiness, creates a fundamental "unfittingness" for direct, unmediated intimacy. The sheer glory of His majesty can overwhelm the finite (Isaiah 6:5), and His absolute moral purity is inherently incompatible with, and must necessarily stand in judgment against, sin and imperfection. His holy presence is like a "consuming fire" (Deuteronomy 4:24; Hebrews 12:29) to that which is profane or sinful.

This profound difference grounded in God's holiness not only creates an unfittingness for unmediated intimacy but also establishes God's unique moral authority and situates Him differently from His creatures. Murphy employs the term "dikaiological order" to describe a shared system of norms, mutual rights, and reciprocal duties that allows the concept of one party 'wronging' another to be meaningful within that system. God's status is as the sovereign, self-sufficient, holy Creator who is not subject to external constraints or limitations in the way creatures are. Because of this immense size-gap God and creatures do not naturally inhabit the same dikaiological order. God does not operate under the same framework of mutual obligations that governs creature-to-creature relationships. Recognizing this distinction helps us to understand why certain divine actions or commands recorded in Scripture, viewed solely from a human, creaturely perspective, might appear problematic. They may stem directly from God's unique status and role as Creator and Judge, operating according to norms appropriate to His perfect holiness and the vast gulf separating Him from creaturely finitude and imperfection.

It is this unique status and essential holiness that, as Murphy argues, gives rise to "requiring reasons." These reasons are distinct from "justifying reasons," which might make an action permissible, good, or understandable. For example, God's love provides a justifying reason for Him to create or to show mercy. A requiring reason creates a rational obligation or compulsion to act (barring counter-reasons), while a justifying reason merely creates a rational permission or option to act. The concept is crucial in thinking about morality and divine action. It addresses whether certain values or situations generate reasons that demand a specific response from a rational agent (like God) or simply make certain responses good or allowable. Requiring reasons stem necessarily and directly from God's own nature or status as the perfectly holy one. They concern what is fitting or even necessitated for God to be the holy God He is (God qua God). In this context, God's holiness provides Him with powerful requiring reasons to maintain a certain separation or distance from sin, evil, and imperfection. For the absolutely perfect and holy God to enter into unmediated, unqualified intimacy with profound imperfection and moral evil would be fundamentally "unfitting" to His nature. It would compromise the very integrity of what it means for Him to be holy. Thus, while justifying reasons rooted in love might motivate God's benevolent actions towards His creation, the requiring reasons rooted in His holiness dictate the necessary conditions and inherent separations involved in how a perfectly holy God relates to a deficient and defective world.

Yet, despite this vast gap and the requiring reasons necessitating a degree of separation, the biblical narrative reveals God's gracious initiative to bridge this divide through the mechanism of covenant. The existence and significance of covenant are underscored by the size-gap it seeks to traverse. Covenant represents God's voluntary and profoundly gracious act to establish specific, structured relationships. This is what Murphy refers to as "cooperative activity" with creatures He is not naturally obligated to engage with in such a manner. In initiating a covenant, God freely chooses to place Himself under certain self-imposed obligations, defined not by external compulsion but by His own perfect, holy character and His faithful promises (e.g., His covenant promises to Israel). Within this divinely initiated covenantal framework, God establishes the terms and possesses the unique authority to relate to humanity and issue commands in ways that reflect His will and character within that specific relational structure, ways that might be impossible or inappropriate outside of it. These commands then function as expressions of His holy nature and sovereign will for His covenant partners.

Why God Cannot Intend Evil

In Chapter 7 of Divine Holiness and Divine Action, Murphy argues that God cannot intend evil because doing so would violate God's absolute holiness. Again, the holiness framework posits that God, due to absolute perfection, possesses requiring reasons—reasons God must act on unless there are adequate contrary considerations—to avoid intimate relationships with anything deficient, defective, imperfect, or limited in goodness, which includes evil.

Although God might countenance evil (accepting it will result from a choice) as a foreseen consequence of achieving some other intended good, intending evil is fundamentally different. Thus, Murphy emphasizes a crucial distinction between merely foreseeing an evil outcome and actively intending it. When an agent intends a state of affairs, even as a means to an end, achieving that state becomes partially constitutive of the agent's success. The realization of the intended object defines the success of the action. In contrast, a merely foreseen outcome, even if it serves as evidence that an intention was carried out successfully, is not itself part of what constitutes that success. The agent can remain alienated from it.

Therefore, if God were to intend evil, that evil's coming into existence would be intrinsically linked to the success of God's own action. The obtaining of evil would partially define God's success as an agent, rather than being merely an unwelcome byproduct or side effect of achieving a separate, good intention. This establishes an extraordinarily intimate relationship between God and the intended evil, where the evil itself is something God is set on achieving and forms part of God's successful agency.

This necessary intimacy involved in intending evil directly conflicts with God's absolute holiness. Because holiness gives God requiring reasons not to stand in such intimate relationships with deficiency and evil, God cannot intend evil. This argument from holiness provides a powerful reason, distinct from purely moral considerations, why intending evil is incompatible with the nature of an absolutely perfect being.

Applying this to Rauser’s theological dilemma, which we discussed at the beginning of this post, given that genocide is a moral atrocity—an unqualified evil—God cannot intend genocide. A similar point applies to ethnic cleansing and the targeting of innocent noncombatants. God cannot intend such evils as His ultimate aim or Target. Therefore, when analyzing biblical commands involving such horrific outcomes, CVE insists that God's actual intended Target must be identified as a distinct good consistent with His character (e.g., executing justice, preserving the covenant), while the tragic evils involved must be understood within the interpretive framework as foreseen consequences of the Mode employed in that unique context, rather than the intended goal itself.

Divine Character as Moral Standard and Source of Virtue Targets

In addition to God’s holiness, there are moral attributes that form the normative core of CVE. This is the character of God as revealed most explicitly in Exodus 34:6-7. This passage, given immediately before God renewed His covenant with Israel after the Golden Calf idolatry, functions as God's self-description, revealing His essential nature. The key moral attributes identified here are:

- Merciful (rachum): Compassionate, deeply loving, like a parent's tender care.

- Gracious (channun): Showing unmerited favor, bestowing kindness not based on worthiness.

- Slow to Anger (erek appayim): Patient, forbearing, long-suffering in the face of provocation.

- Abounding in Steadfast Love (rav-chesed): Overflowing with loyal, covenantal love and kindness; reliable goodness.

- Faithful (emet): True, reliable, consistent, dependable in word and deed.

- Forgiving (noseh): Bearing or taking away iniquity, transgression, and sin, demonstrating a readiness to pardon.

- Just (naqqeh lo yenaqqeh): Literally "will by no means clear/leave unpunished," signifying God's unwavering commitment to accountability, righteousness, and upholding moral order against sin.

- Intergenerationally Consistent (poked avon): "Visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children... to the third and fourth generation" (Ex 34:7).

- CVE interprets this challenging aspect not as arbitrary collective punishment or direct imputation of guilt across generations for specific acts, but as reflecting the profound and lasting corporate consequences of foundational, persistent wickedness, particularly rebellion against God's covenant and redemptive purposes (the Telos). It signifies that such deep-seated, unrepented corporate hostility can have enduring effects that God, in His unique role as Sovereign Judge operating within the covenantal Field and according to His revealed character, may address over time according to His own timetable and purposes. This aspect of divine justice, revealed alongside overwhelming mercy and love, underscores the seriousness with which God views systemic, covenant-breaking evil.

These moral attributes are not abstract philosophical ideals. They are the revealed nature of the personal God who acts within the history of covenant relationships. They exist in a dynamic and creative tension, not as contradictions. Following insights from Matthew Lynch (2022), CVE emphasizes that, in addition to holiness, mercy and steadfast love (Hesed) form the central core of God's character, often described as "triumphing over" judgment. Yet mercy and love do not negate or cancel out His commitment to justice and faithfulness. Understanding this ordered relationship and balance is vital for interpreting God's actions throughout Scripture.

CVE integrates Christine Swanton’s Target-Centered Virtue Ethics (2003, 2021) to analyze how these divine attributes function as the source of moral normativity. TCVE views virtues not just as dispositions but in terms of their aims or "targets." Each divine attribute, considered as a virtue, has a characteristic profile:

- Field: The domain or sphere in which the virtue operates (e.g., situations of suffering for mercy; covenant relationships for faithfulness; instances of wrongdoing for justice).

- Basis of Acknowledgment: The specific feature within the field that appropriately triggers the virtue's response (e.g., vulnerability for mercy; existing commitments for faithfulness; nature/severity of transgression for justice).

- Mode(s) of Responsiveness: The characteristic way(s) the virtue acts or responds to its basis (e.g., alleviating suffering for mercy; fulfilling promises for faithfulness; rectifying wrongs/judging for justice). Note: Swanton emphasizes a pluralism of modes beyond simple promotion of good.

- Target(s): The specific goal, state of affairs, or outcome the virtue aims to achieve in that particular context through its mode(s) of response (e.g., relief of suffering for mercy; integrity of covenant for faithfulness; restoration of moral order/accountability for justice).

According to CVE informed by TCVE, acting rightly means successfully reflecting God's character by "hitting the appropriate target(s)" with the "appropriate mode(s) of responsiveness," triggered by a correct perception of the "basis" within the relevant covenantal "field."

Context-Weighted Reasons Shaping Targets and Modes

CVE incorporates a context-weighted reasons approach, drawing on work by Eleonore Stump and Richard Swinburne, to explain how God's immutable character manifests differently in various situations. While all of God's attributes (Mercy, Justice, Faithfulness, etc.) are eternally and equally perfect in His nature, the specific features of a given situation (the "field" and "basis" in TCVE terms) provide stronger reasons for expressing certain attributes more prominently than others in that context.

For example, a situation involving extreme, unrepentant wickedness (basis) within the covenant community (field) might heavily weight the reasons associated with divine justice, making its target (e.g., judgment for accountability) paramount. Conversely, a situation of genuine repentance and vulnerability (basis) might heavily weight the reasons associated with mercy, making its target (e.g., forgiveness and restoration) the primary focus.

This dynamic weighting, driven by the context interacting with God's full character, determines several key aspects of a morally right (God-reflecting) action:

- Which divine virtues provide the strongest motivating reasons in that specific scenario.